A friend of the old waterfront, Joseph Sciorra (of Queens College’s John D. Calandra Italian American Institute), was entrusted several years ago with a cassette tape of a rare old Frank Sinatra 78 rpm recording. He recently posted it on YouTube: Forty-eight seconds of the great singer in his prime, making a scratchily sincere endorsement for the anti-Mob candidate for Congress in Red Hook in 1946. Vincent ‘Jim’ Longhi was a young waterfront lawyer just back from the war that fall that the Sinatra booster record played from trucks all over Brooklyn’s 12th district on his behalf.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yd1OKRvzaIo

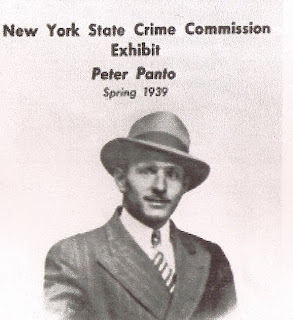

Longhi was thirty years old when he dared to run for congress in an anti-Mafia campaign. The Democratic candidate backed by the Camarda clan was traditionally a lock, leaving the forlorn Republican nomination wide open for Longhi, whose politics were closer to the leftist American Labor Party, which would also endorse him. “Since ninety percent of the workers on the Brooklyn waterfront were Italian,” he told me sixty years later, “and I’m an articulate young Italian about to be a lawyer, we could capture the Republican nomination, and we did.” It was a sign of how close a Republican majority finally seemed in 1946 that New York party leaders tolerated candidates as left-leaning as Longhi, who found “hundreds of longshoremen who remembered and worked with [martyred longshore leader] Pete Panto who thought, ‘Someday we’ll get the Mob out of there.’ They became my campaign workers. The campaign and the struggle against the Mob rackets became synonymous.”

Longhi had been drawn to waterfront politics through his father Joseph, a combative socialist who fled Italy to eventually become a docks organizer in New York when the International Longshoremen’s Association was an emerging union dominated by a former tugboat captain, President T.V. O’Connor, and the onetime head of the Five Points Gang, Paul Vacarelli, who “Irished” as Paul Kelly. “When my father married my mother,” Longhi recalled with a son’s awe, “he had a bodyguard of eleven men, eleven Italians with ice picks!”

Jim Longhi’s life took the first of its many unlikely jags when as a law student at Columbia he met Woody Guthrie on a New York City subway and ended up playing in a trio with Guthrie and Cisco Houston in the Merchant Marine. They enlisted together in 1943, a time when German submarines had sunk over seven hundred Allied merchant vessels and killed six thousand seamen in the North Atlantic. (New York’s wartime brownout was designed to give departing ships less of a targetable silhouette against the city’s lights for German U-boats preying offshore.) The singing trio were not spared the odds—Longhi had two feighters sunk beneath him; the Willy B. was torpedoed and chased by a U-boat in the Atlantic, and the Sea Pussy was ripped open by an acoustic mine off the African coast. He lost half his hearing in the war.

Back home from his improbable tour young Longhi’s congressional strategy was simple: The theme would be the racketeers, or “bucking the Mob.” The election would not be a door-to-door effort but would be fought on the piers. “We weren’t campaigning for parks or better schools but ‘Stop the shape-up. Stop the speed-up.’” These were the concerns of thousands of local Brooklyn longshoremen, whose lives were controlled through a half-dozen “Camarda locals” that covered the five miles of shore between the Brooklyn Bridge and Twentieth Street.

Longhi’s anti-Camarda campaign gained him the respect of local oddsmakers, attracted “intellectual” sympathizers such as the playwright Arthur Miller as well as an unlikely but dangerous ally. He soon found himself in a dark quandary, running such a strident campaign against the Camardas that he caught the eye of their waterfront rivals. Even as Congressman John J. Rooney called him a Communist “importation,” Longhi’s reform candidacy dovetailed with the ambitions of the Anastasia brothers. Albert Anastasia had survived the dismantling of Murder Inc., gaining his American citizenship training longshoremen for the Army in Pennsylvania during the war. With peacetime, he settled back into Brooklyn as powerful as ever, waiting for any sign of weakness to move against the Camardas.

“The Brooklyn waterfront was broken up into smaller locals, more easily controlled, and our fight was for one union, one local,” Longhi recalled near the end of his long life. “Simultaneously, you had the Lord High Executioner himself, Albert Anastasia, who wanted a palace revolution, knock off the big guy [the Camardas] and take control… Temporary alliances were made through Albert’s brother, Tough Tony. The Anastasias wanted to take Camarda and company down, that’s what we wanted to do, so in a sense we’re allies.” Longhi compared this “painful” coalition to the situation where “the American Democrats, who regarded Russia as a monster, could make temporary alliances so they could defeat the devil himself, Hitler.” The effects of the deal were immediately clear when Longhi’s campaign workers learned of a plan to silence him.

Early one morning as he was belting out his stump speech to the crowd stamping into place for the shape-up, “My guys were tipped off” that Camarda men were stationed on the rooftops above him, poised to dump garbage cans filled with dead fish down on the candidate. Longhi’s workers relayed the news of the loaded cans along the ground until it reached Anastasia’s people. In a strange-but-true moment, the rooftop operation was stopped in its tracks on Albert’s private word and Longhi’s anti-Mob speech resumed.

Egged on further by Sinatra’s booster record that played all over Red Hook, Longhi had made a fight out of a mismatch by election day. “Longhi has been making a spectacular campaign,” observed the Times, “and is given a chance of election.” With the disparate endorsements of the Republicans, American Labor Party, and the Daily Worker, and despite the private approval of the Anastasias, Longhi lost to Rooney by a respectable five thousand votes.